- Home

- Lynne Kositsky

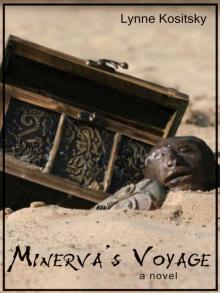

Minerva's Voyage

Minerva's Voyage Read online

MINERVA’S

VOYAGE

MINERVA’S

VOYAGE

Lynne Kositsky

DUNDURN PRESS

TORONTO

Copyright © Lynne Kositsky, 2009

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise (except for brief passages for purposes of review) without the prior permission of Dundurn Press. Permission to photocopy should be requested from Access Copyright.

Project Editor: Michael Carroll

Copy Editor: Cheryl Hawley

Design: Erin Mallory

Printer: Webcom

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Kositsky, Lynne, 1947—

Minerva’s voyage : a novel / Lynne Kositsky.

ISBN 978-1-55488-439-1

I. Title.

PS8571.O85M46 2009 jC813’.54 C2009-903259-7

1 2 3 4 5 13 12 11 10 09

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for our publishing program. We also acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program and The Association for the Export of Canadian Books, and the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Book Publishers Tax Credit program, and the Ontario Media Development Corporation.

Care has been taken to trace the ownership of copyright material used in this book. The author and the publisher welcome any information enabling them to rectify any references or credits in subsequent editions.

J. Kirk Howard, President

Printed and bound in Canada.

www.dundurn.com

Images from Henry Peacham’s Minerva Britanna, used by permission of Special Collections at Middlebury College, courtesy of Professor Timothy Billings. Some have been digitally altered from their originals.

Dundurn Press Gazelle Book Services Limited Dundurn Press

3 Church Street, Suite 500 White Cross Mills 2250 Military Road

Toronto, Ontario, Canada High Town, Lancaster, England Tonawanda, NY

M5E 1M2 LA1 4XS U.S.A. 14150

For Michael, my life partner;

Roger, my writing partner;

and Tom, my sparring partner.

CONTENTS

Chapter 1: From the Frying Pan to the Fire

Chapter 2: Robin Starveling: A Playful Name

Chapter 3: In the Belly of the Boat

Chapter 4: Emblem Enigma

Chapter 5: New Alliance

Chapter 6: Damn that Fly!

Chapter 7: Scratcher’s Ambitions

Chapter 8: Horrible Proule the Ghoul

Chapter 9: It’s a Cipher!

Chapter 10: Pelted by Mary and Rain

Chapter 11: No Hope!

Chapter 12: Over the Rail

Chapter 13: The Visitation of St.Elmo

Chapter 14: Goodly Land

Chapter 15: Opening the Chest

Chapter 16: Lost in a Dream

Chapter 17: Deciphering!

Chapter 18: In the Spinney

Chapter 19: Storm Sighting

Chapter 20: They’re Gone!

Chapter 21: Hellish Head Bang

Chapter 22: Eating and Telling Tales

Chapter 23: The Path and a Bath

Chapter 24: Raising a Storm

Chapter 25: Early Rising

Chapter 26: A Stolen Hoard

Chapter 27: Small Beer and Mince Pies

Chapter 28: Underneath the Trees

Chapter 29: Robin’s Find

Chapter 30: Evil Scratcher

Chapter 31: In the Labyrinth

Chapter 32: No Mercy!

Chapter 33: The Escape

Chapter 34: Hidden and Discovered

Chapter 35: Entering by Invitation

Chapter 36: Bastard Prince

Chapter 37: On His Head the Crown?

Chapter 38: Out of the Cave and into Danger

Chapter 39: Keeping the Treasure

Author’s Note

Acknowledgements

CHAPTER 1

FROM THE FRYING PAN TO THE FIRE

I was stolen off the streets of Plymouth in the year of our Lord sixteen hundred and nine, by Master William Thatcher, better known as Scratcher, whose name and nickname I came to know in due course. It was the second of June, upon a Friday noontide, and the weather was waxing hot. The wind blew salt across the town. A multitude of holes in my hose allowed the damp breeze to reach through and cool my body. Scratcher had his sleeves rolled up above his elbows. We collided at the intersection of New Street and a small alley, where I was knocked on the head by Scratcher’s wooden chest, which he carried on his shoulder and which travelled, at least in part, ahead of him. I fell down, stunned by the blow.

“Where do you live, boy?” Scratcher demanded. He dropped his chest and pulled me up by the ear.

“Nowhere, sir,” I said. And this, for the moment at least, was true.

“Who are your parents?”

“None, sir.” I felt a single tear drip down my cheek.

“Any who care?”

“No.” This was true enough also. I sniffed.

He let go of my ear. “What is your name, boy?”

“Forgotten,” I said. In fact, my name was Noah Vaile. I was more than glad to lose it because it sounded like “No Avail.” Widow Oldham always made nasty cracks about it. If any of the other students asked me to do anything, she’d cackle and say: “Don’t you see? It’s hopeless. It is to Noah Vaile that you speak.” It made me feel like a failure before I was even out of the starting gate. Returning to the present, I rubbed my forehead, which I was certain must be dented by the chest.

“Hmm. I will name you anew when the mood strikes me.”

I threw him my best questioning look.

“I am in need of a servant: to fetch, to carry, to sharpen my quills.” He was in need of a servant with no family connections; that was clear enough. “Pick up my chest.”

“Well,” said I, thinking as fast as I could while rubbing my head again.

“Stop that rubbing at once. Pick up my chest and be sharp about it.”

I didn’t like him. He was thin as a snake and looked horribly nasty, with two deep dark lines that ran from his eyes to his chin. And he kept scratching himself; he went at the scratching something furious. Besides, I was still weighing him and his intentions up. Who is easier to dispose of, after all, than a boy with no family? I could, in fact, see the tip of a knife hilt in his belt. It boded ill. But without him my prospects were dim, my next stop almost certainly the alms house. He had arrived, true it is, straight from Fortune, without turning left on the way.

My parents had vanished in a dense fog — the haze of the past, and also the very real smokiness of Plymouth town. Mistress Oldham, the schoolkeeper, had taken me in out of a confused blend of pity and laziness — she needed a slave — but had recently ejected me for setting rats free in the schoolhouse on Saturdays, and myself free during the week. I should have been studying and doing the housework, but was a certified truant who preferred pilfering to lessons and skivvying duties. The week she threw me out I pinched a chicken leg, a mound of apples, and a pigeon pie, all from St. Nick’s market. There is a streak of wickedness in me, I’ll willingly admit, but I’ve learned to live with myself as I am. There is no fixing wickedness: it arrives with a whoosh and a flash of its own accord. It makes no prior announcements. Sometimes my actions surprise even me.

“General truancy, is it? I can’t abide general truancy even more than I can’t abide rats,” Oldham had screeched two weeks ago, pinching my ear just as

Scratcher had just now. Adults seem to be overly fond of ear gripping, pulling, and pinching. In my case, it is their easiest hook to hang on to, the rest of me being too thin and slippery to grab a good handful of. Oldham knew nothing of my stealing, happily, or she’d have turned me over to the judge, and I’d now be hanged by the neck — boots dangling — until dead. I’d seen hangings enough in Plymouth, the convicted giving me a penny once or twice to pull hard on their legs after the drop and help their departure along.

I didn’t want any young cozener pulling on my legs, thank you very much. I learned to run fast, really fast, so that I could outstrip the barrow boys whose stalls I nicked from. So if Oldham ever did find out my crimes, which, God knows, were hang-worthy, and decided to haul me to the judge, likely she wouldn’t be able to catch me. In any case, her corns and carbuncles slowed her down. So did her enormous belly, which, when she so much as shifted from one foot to the other, quivered like a bowl of blancmange under her gown.

“Careful, boy. Stop daydreaming. There’s treasure inside,” Scratcher scolded now. I turned my attention back from Oldham’s fat gizzard to his fat chest. His chest of the wooden, not the fleshly sort, I hasten to add. His fleshly chest looked more like a mine that had misfortunately suffered a cave-in.

“I haven’t so much as touched the chest yet, sir.” But my pulse twitched a couple of times. Spanish dollars were already glittering, big and round as silver plates, in my imagination. Treasure, was it? Scratcher could prove really valuable to me. My eyes must have lit up like candles on Sunday.

“Not that kind of treasure, you ignoramus. Intellectual gold. Poems and maps.” His knotty face slanted sideways, and his loose neck skin creased into a wattle.

“Oh,” said I, trying to ignore the fact that he looked like a demented cockerel and concentrate instead on his words. I’d spent two years in school trying to avoid poems and maps. But though I say so myself, I was sharp as a rapier, and much learning had rubbed off on me. What kind of poems and maps might these be? They were certainly not like those in the writing and cosmography lessons given by old dry-as-dead-bones Oldham. They would be treasure maps. With an X marking the spot. Ho ho. A shard of excitement flew up my arms, piercing my heart.

“Are you coming or not, sirrah? The hour is at hand.” Scratcher managed to sound pompous and religious at the same time.

“What hour is that, sir?”

“You’ll find out soon enough.”

I chewed on the inside of my cheek loudly. I gestured into the northwest wind. But everything was performance, with him as spectator, because my mind was already made up. I had nowhere else to go, and there was also that treasureful mystery that had just cut deep into my heart and now tickled my brain. He cuffed me on the head. I jerked the chest skyward. He jumped back in momentary alarm, and I laughed in my mind. Then he nodded, turned, and veered along the cobblestone alley. I followed.

CHAPTER 2

ROBIN STARVELING: A PLAYFUL NAME

The hour was the hour of sailing. Unbeknown to me, I had been carrying a sea chest. If I’d have realized that the idiot was going to sea, I’d never have budged from my begging corner. I was terrified of the ocean. I was even scared witless of wells, would throw a rat hellwards to hear the dark splash. But I’d never look over the rim for fear of drowning. I’d seen others drown in the past, not in wells but with their ship almost to shore, their arms thrust above the waves, their voices thick yet shrill. Later there had been no voices, just the roar of the ocean and the nearby snarl of breakers. That was worse than the screams. Just like the silenced howls of hanged thieves and murderers, when they swung back and forth in the wind: The sound of no one. Yet here I was on a boat, the Valentine, as we rocked away from the dock. I’d tried to bolt at the last minute, treasure notwithstanding, almshouse notwithstanding. But Scratcher, as I came to know him, had tripped me up, shouldered his chest for once, and dragged me aboard by the hair, confirming with his treatment of me my already dubious impression of his nature.

Fearfully, I looked to the sea. We were in the company of other boats, their rigging tight as sinews, their sails slung out like women’s petticoats. I counted six ships and two smaller pinnaces, all stuffed with souls. We were no different. Our own deck was as busy as the Bear Gardens at Candlemas.

“Bound for Virginia,” an important-looking man shouted.

There was a ragged hoorah from the crowd, but a few travellers, men and women after my own heart, looked white as Monday’s washing.

“Let me off. I don’t want to go,” I yelped.

“Don’t worry. That’s Sir George Winters, our admiral,” said a dark-haired boy, pointing to the important-looking man. The boy was slightly smaller and probably younger than me. He wore an old black glove on his right hand, for reasons unknown, and sounded proud. “The admiral’s a good seaman. He’ll take care of us. But don’t get on the wrong side of him.”

“Thanks,” I said. “I’ll remember not to.”

Winters didn’t appear too frightening, not compared to some I’d come up against in the past, but I was terrified in a more general way anyhow. Virginia was the other side of the great ocean. The trip could take months. Maybe, despite what the dark-haired boy said, we’d fall off the edge of the world on the way. Or go down with our arms flung up, like the drowned sailors. I hadn’t spent my time avoiding hanging so I could plummet to the bottom of the ocean.

“Virginia?” I asked Scratcher, still not really believing.

He didn’t respond. He was busy scratching his arm, his face to the wind, his graying hair wisping out behind him.

“Chin up, Ginger Top,” said a sailor, who was swabbing the deck. He smiled crookedly and rested his arm on one of several cannons. It was huge, snub-nosed, and black, and gave me not a whit of confidence. Were we to fight pirates, then? Or the vessels of the Spanish Main of which, even as a landlubber, I had heard too much?

“There’s a name for you, sirrah. Master Ginger Top.” Scratcher grinned, then spat through a hole in his teeth into the huge expanse of water beside us.

“Not likely, sir.” Carrots was bad enough, and I’d heard that too many times to count.

He thought for a moment. “Starveling, then. Robin Starveling. You do look pared down to the bone, and that’s a fact.”

I frowned. Who was he to talk? He was skinny as a hungry rat. His hands had the scrawny look of hens’ feet. But Starveling was as good a name as any, I supposed, though Heaven knows where he’d dragged it from.

“There was one called that in a play,” Scratcher said, as if in answer to my thoughts, “when I was working in the theatre. He was just about as dim and as thin as you are.”

Well then. Affronted I might be, but there was no way, after all, that I’d trust my real name, which was now buried in my brain, to Scratcher. He’d ridicule it for sure. Besides, the less he knew the better. Meanwhile, the more I found out about him the happier I’d be. Robin Starveling, eh? It had a ring to it.

I looked at the cannon again, fear rising in my throat.

“No need to be afeard, boy, of the sea. We s’ll all make our fortunes.”

“They say that the trees are high as mountains and the river by Jamestown wide as an ocean,” whispered the dark-haired boy. He turned suddenly and clambered up the rigging. I kept my eyes down, too dizzy to look up. He disappeared from my view in a twinkling.

“Aye. An’ the streets is paved with gold and the shores awash with diamonds and rubies. Ain’t that so, Master Scratcher?” The sailor winked.

“Don’t be stupid, Piggsley. There are no streets. And no jewelled sands. And the name, as you very well know, is Thatcher.”

“Aye aye, sir.” Piggsley tipped his threadbare cap.

Scratcher was now watching an ample-hipped woman in a red skirt as she swayed across the deck. When she disappeared below, he licked his thumb, dabbed mud off his hose, and slid slick as an eel through the hatch. “I must speak to her about the sumptuary laws,” he said, halfway thr

ough. “Poor woman that she is, she has no right to be dressed in scarlet.”

“That’s Mary Finney,” obliged Piggsley. “She does services for gentlemen.”

“Does she indeed?” Scratcher grinned.

“Laundry services, I meant.” But Scratcher was gone. Piggsley screwed his finger around his ear thoughtfully. “There’s Will Scratcher, er, Thatcher, for you,” he said. “We calls him Scratcher cause he’s always scratching sundry parts of himself. Jes’ now it was his belly. Other times he ain’t so polite.” Winking at me, Piggsley went on, “A single whiff of woman and he’s away. Then he says it’s his great sin. I seen him on other voyages.”

So Scratcher had a weakness for women, did he? And Scratcher had also been on other voyages. I tucked these tidbits into the back of my brain in case I should have need of them. Then I upchucked my last meager meal of bread and wiped my mouth free of sick.

“Steady there, lad. We’s barely out of port.” Piggsley finished sweeping our part of the deck and moved on.

Sea travel didn’t bode well for me. I felt better for being empty, though my mouth tasted bitter as aloe and the dizziness remained. And the blasted chest still needed to go down to the hold. No one would shift it except me, and I must have walked it damn near five miles this day, in and around Plymouth. I would best Scratcher for taking me to sea, I swore silently. And for making me carry his vile heavy chest crammed with maps and poems all around the town. It might take five days. It might take fifty. But I would best him.

CHAPTER 3

IN THE BELLY OF THE BOAT

We were sailing southerly and somewhat westerly. Or so Piggsley had told me. It was hot as hellfire below and stank of mold and filth and foot-rotted boots. The smell would surely choke us by the time July arrived, that’s if we were still alive then.

Minerva's Voyage

Minerva's Voyage